I was lucky enough to attend three conferences last week, two virtual, one physical.

The first was the “DevOps Enterprise Summit” hosted by Gene Kim from the Las Vegas timezone. A keystone event worldwide for the transformation of software development, it has thousands of attendees.

The second was a “Intersection of DevOps and Security with DevSecOps" from GitLab, run out of our time zone but a little further north in Singapore.

And the last was the Copland Leadership lecture organised by CEDA in Perth and delivered in person by former Foreign Minister Julie Bishop at the PanPacific.

Each presented a different perspective on the state of play in our industry and in the world – and in the challenges that lie ahead for us all.

DevOps Enterprise Summit

From the DevOps Summit two things stand out.

The first is that Australia and Perth lag the world when it comes to high performance software development.

This is not particularly surprising. In Perth we don’t have the tech giants of Silicon Valley or of Shanghai and the swarms of developers that support them. We are also weak in the industries that are driven by software. In a worldwide review of DevOps maturity, the top three industry segments were retail, finance and telecoms – mining and resources didn’t even make the list.

While I think there are many bright spots of innovation in Western Australia it is against a much wider backdrop of ‘heritage’ practices and mediocre technology. We might be blessed with the best beaches and climate in the world, but our uneasy embrace of technical innovation is well documented – from Sarich's orbital engine to startups like Canva or lesser known businesses like carbon fibre manufacturer Quickstep – Australia’s answer to California we are not.

The problem seems to lie in our ability to collaborate effectively - across industry, education and government. The rhetoric in this area is loud but the evidence is thin on the ground.

And while there is widespread acknowledgment of the importance of STEM and software in the future of all industries, we still import much of our technology expertise from overseas. It’s as if we can’t believe the people we went to high school with could be world leaders in any serious field.

Strangely, with the borders closed our technology sector has continued to thrive.

The second observation is that COVID represents exactly the kind of challenge that requires agility to overcome. And it won't be our last.

While those of us in Perth and Australia in general are entitled to feel smug about our COVID numbers, the relative lack of infection has meant that we haven’t really had to deal with the consequences. We’ve delivered some short-terms workarounds through the heroic efforts of our people, but we haven’t achieved the kind of structural flexibility that will be required in the years to come.

I think the current Western Australian government is acutely aware of that from all the initiatives around hydrogen, agriculture and the METS sector. The age old aphorism that we need to diversify has taken on a new urgency in the current reality, but more of that later.

The rest of the world is definitely not resting on its laurels – the spectre of disruption is real to every business in every industry. Disruption was a clear and present threat even before COVID, the pandemic has just thrown it into sharper relief. As W. Edwards Deming (possibly) said “Survival is optional. No one has to change.”

In one presentation from Vegas, the CTO of American Airlines explained how, in response to a future in which COVID is endemic, they rolled out a completely touchless check-in kiosk in just six weeks.

This was at the culmination of a three year transformation journey where they progressed from the driving the adoption of DevOps, to driving metrics to driving the outcomes of their software development process.

In our observation, the very best of Perth’s technology teams are barely in the second year of that journey.

What this meant in practice was that the team tasked with rolling out the touchless system only needed to be given the goals they had to achieve - to reduce physical contact to zero, to improve processing times by 50% and to maintain customer satisfaction – and the means were left up to them. And this was delivered in the course of normal business, the only impact COVID had was to shift the goal posts a little.

The best talk from Vegas however was from the “Kessel Run” – an initiative that successfully ‘smuggled’ DevOps into the world's largest bureaucracy, the US military.

Adam Furtado, the Chief of Platform for the Kessel Run opened his talk by describing how “ancient software systems” led a US AC-130 gunship to destroy the wrong building in Afghanistan – in his words “the failure of business outcomes for the US Air Force doesn’t involve a loss of revenue or a loss of customers, it involves a loss of life.”

The name “Kessel Run” was an acknowledgement that bringing these techniques to the Air Force was always going to be viewed as an insurgency by the incumbent forces in the Empire-scale bureaucracy – in his words “it wasn’t a rebellion, it was a revolution”.

The goal of the Kessel Run was to bring modern software development to the Air Force, to create “a software company that could win wars” – and they weren’t talking about cyberwarfare, they were talking about software enabling the conventional work of the Air Force. By deploying common and well trodden DevOps techniques to a pilot project they were able to deliver savings of US$200k/day in aircraft refuelling within weeks and, by iterating on the problem, nearly US$13m of savings per month.

Their initial success could have gone unnoticed had not an astute Deputy CIO, Lauren Knausenberger noticed that the project had not only delivered faster, and cheaper than any other project it was also a more intrinsically safe development process.

Lauren understood that the security automation and monitoring that they had built into their pipelines and their systems delivered what she described as “the most secure software deployment process in the Department of Defence.” By working with auditors and cybersecurity teams she was able to accredit the pipeline which meant that software deployed via that pipeline was automatically accredited and could be deployed to “warfighters” multiple times per day - effectively removing the last manual gate in the software deployment process.

Stick that in your risk management pipe and smoke it.

In about three years, Kessel Run has grown from 5 to 1300 people with 50 product teams and fifteen different platforms and the growth has thrown up challenges in maintaining the culture and pace of innovation.

But this is a drop in the ocean.

If you think that your organisation is difficult to change, then spare a thought for the challenge that lies ahead for Lauren and Adam. They need to scale their approach to the span more than 600,000 users of Air Force IT systems, but they are excited at the challenge because they understand the prize that can be won.

Navigating the Intersection of DevOps and Security

The GitLab sponsored Singapore conference on DevSecOps was also instructive.

A little closer to home and a little less transformational, it dealt with the “Intersection of DevOps and Security” or DevSecOps as the pundits will have it.

The evolution of the software development lifecycle has put pressure on InfoSec teams to keep up with the pace of change - hence DevSecOps and the ‘shift-left’ automation of security in the software toolchain.

My reflection here was that the panellists from Gitlab, SingTel and the United Overseas Bank were all well versed in the language and metrics of DevOps. The challenge was not in how to adopt DevOps or where to start - the assumption was that you were already well on that journey and you just had to integrate security practices into the DevOps machine that powers your software development.

One discussion focussed around the State of DevOps metrics produced by DevOps Research Association (DORA) and embodied in our online game the DevOps Dream. The panellists discussed how to extend the DORA metrics to incorporate a measure of “DevSecOps” maturity - or the maturity of automated security practices.

Another recurrent theme was the rise in security issues and in threats that organisations are seeing as more workloads and teams move online. The rapid adoption of platforms like Zoom and the disruption to traditional income streams for scammers has led to an explosion in COVID related exploits. They leverage the vulnerable seams between new digital systems and legacy security processes which aren't keeping pace.

Again the need for agility is palpable.

The CEDA Copland Leadership Lecture

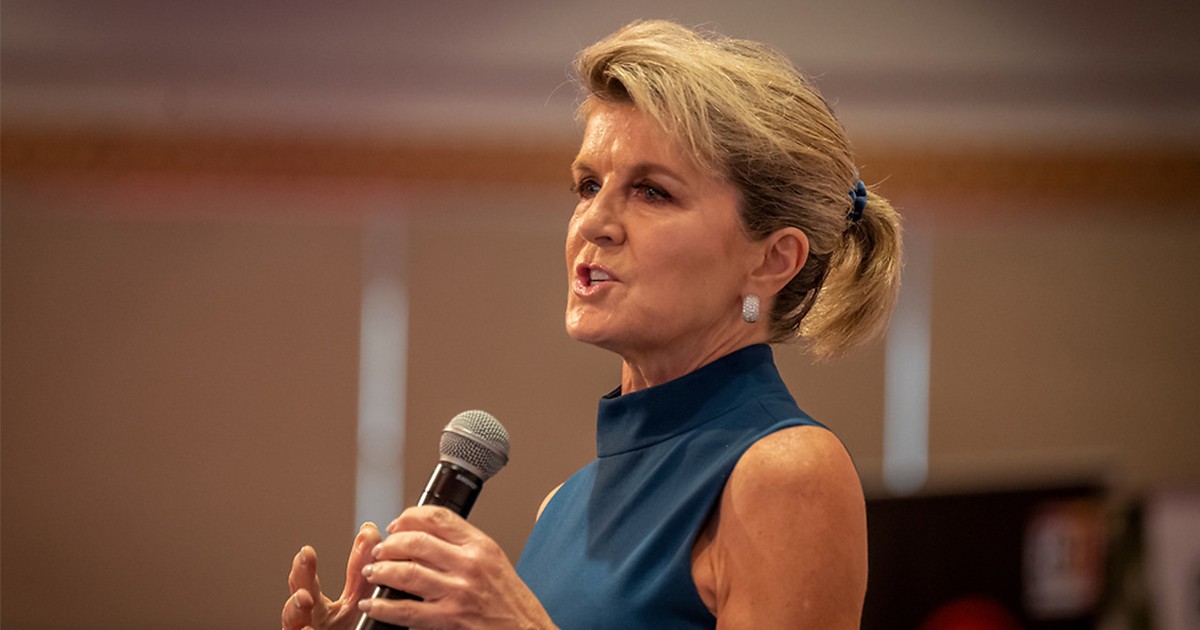

The last of my insights comes from the CEDA Copland Lecture, delivered by Julie Bishop.

Julie served as Foreign Minster of Australia for five years and is the current Chancellor of the Australian National University. Her insight into the nature of leadership from her time in the Australian parliament and at the United Nations was instructive enough, but it was her references to ‘mega-trends’ that I was most interested in.

There are four basic trends that were well underway before COVID struck and that will continue to shape our world for the next fifty years.

They are:

- Climate change and climate adaptation

- Rapid urbanisation and demographic change

- Shifting geo-political power

- And the rise of Technology v4

The last of these has been variously described with terms like machine learning or the Internet-of-Things or automation but it is in fact the convergence of all these which threatens to radically reshape our world.

Whether the reshaping will be positive or negative depends largely on your outlook and, dare I say it, your demographic profile.

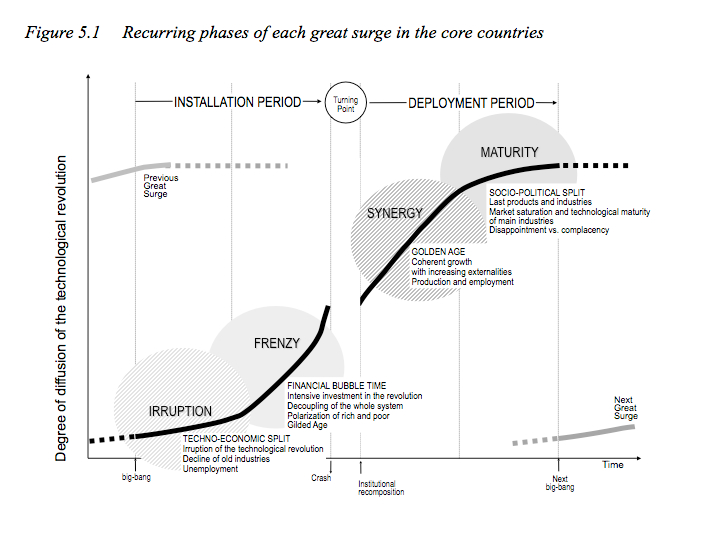

I prefer the viewpoint of the Venezuelan economist Carlota Perez who studied the patterns of technological revolution. In her work she studied four past revolutions - the industrial revolution, the age of steam, the age of heavy engineering and the age of the automobile – and has predicted the course of the fifth revolution – the age of information.

Perez’s model predicts an ‘installation’ phase where technology is developed, followed by a sharp period of disruption and then a ‘deployment’ phase where the technology becomes widely used and leveraged for the greater economic benefit of society.

The disruption phase or inflection point is characterised by the rise of populist leaders, increased inequality leading to social unrest and massive systemic upheaval that is triggered by an external event.

Sound familiar?

In the last revolution, the automobile, it was the rise of Hitler and Stalin and the descent into WWII that characterised the disruption phase.

The good news is once the system adjusts we can expect a golden age of productivity, wealth and increased equality.

After WWII there was a widespread understanding that the massive industrial sector could only be repurposed to consumer goods if consumers had the surplus funds to buy them. So there was a rise in the standard of living that led to a virtuous cycle of consumption.

The bad news is that no one, not even Ms Perez, can predict how long the disruption phase will last.

The trigger that will end the disruption phase will be the structural change in our environment brought on by a new wave of business and political leaders. Leaders with the vision and the narrative to tap into the zeitgeist and change laggard institutions to the wider benefit of society.

This is a sentiment that Ms Bishop echoed in the Copland Leadership address.

COVID is a specific manifestation of the challenges underpinning the mega trends that are shaping our world. Once we have COVID under control the other trends will continue to drive wedges into the seams in our global society.

And out of those four mega-trends, technology is the only one that looks anything like a solution. It definitely has a role to play in climate change and urbanisation and demographic changes (think coping with an ageing population) but it probably also has a role to play in shifting geo-political power.

For example, while a lot of rhetoric has been spent on local manufacturing and shoring up domestic supply chains, forward thinking organisations like the US Air Force have recognised that a digital supply chain is just as important to success - and considerably easier to influence.

What are we doing in Western Australia to shore up our digital supply chain?

Or even in across Australia?

The digital sector in Australia is fragmented and divided. While there is a lot of positive spin on collaboration between industry, government and the education sector the reality on the ground is not so much “we’re all in this together” as “every man for himself”. Initially that might makes sense as every organisation looks to its own survival but in the longer term the challenges will require our combined resources to overcome.

Countries like Israel, Singapore and even New Zealand have done a much better job of integrating automation, data, and new technology into their legacy economies.

COVID-19 and hard borders have forced us to realise that while we live in a networked, globalised world we have not yet defeated the tyranny of distance and that innovation starts at home - to purloin a phrase.

The countries and businesses that develop flexible and robust digital ecosystems will be the ones able to exploit the tide of change for the benefit of their citizens, workers and shareholders.

That change will have to be driven by leaders with vision, understanding and foresight.