This post is part of a series covering our development of DevOps Dream:

- Having a DevOps Dream

- Living the DevOps Dream

In my previous post I covered some of the background to DevOps Dream and where the idea came from. In this post, I'd like to give some insight into how we Lived the DevOps Dream: how DevOps influenced the way we delivered DevOps Dream.

Once the dust settled after our offsite team day, we took time to reflect and define our goals. We identified three primary goals:

- User base: 100K players by end 2020.

- Engagement: 10% of players replay at least once.

- Positive sentiment: 10% of players talk positively about the game publicly.

Starting with the end in mind, our BHAG was to receive 100K users by the end of 2020. To date, we have recorded about 1500 users, so unless magic happens we are unlikely to hit that target. We achieved a more realistic sub-goal though: 1000 users within the four weeks. Analysing the disparity, achieving our major goal was only realistic either through expensive marketing or if the game went viral. Whilst we would love DevOps Dream to break the internet, it isn't a likely outcome with our chosen marketing spend.

Our more modest goals for engagement and positive sentiment were achieved with flying colours: nearly 20% of users replayed at least once with an average session duration of 9 minutes. And a social media sentiment analysis recorded 90% positive feedback.

We wanted to build something that was quick enough to play in a coffee break, yet had enough depth to make you think and could be used to spark discussion within teams. We are happy that we have achieved our goal.

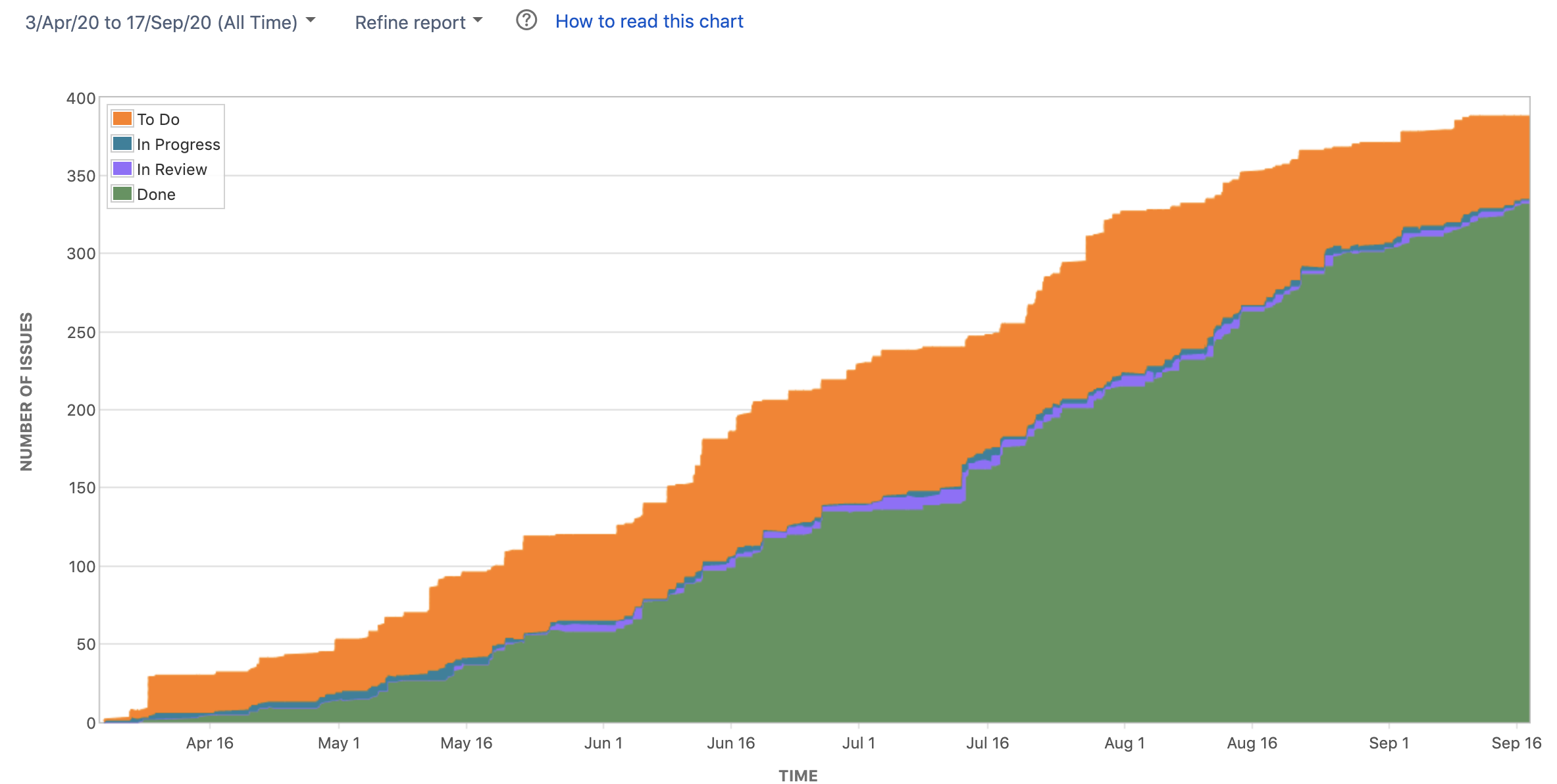

An unwritten goal was to lead by example: demonstrate how effective DevOps practices drive successful business outcomes. Our project retrospective paints a clear picture:

As a software delivery project, DD was extremely successful:

- We went from concept to launch in 4.5 months / 167 days

- We completed 332 issues and 85% first pass complete (15% rework)

- We had very low WIP and good average cycle time of 2.5 days

- By DORA’s own metrics we achieved Elite status:

- Deployment Frequency: We averaged 2.5 deployments per day, with a maximum of 9

- Lead Time to production: averaged 52 minutes

- Change Failure Rate: < 5%

- Time To Restore: N/A

* We only had one issue where we chose to invoke our incident response process. The issue was identified out of hours and did not affect user function so investigation/resolution was deferred to the next business day. Therefore we chose to include it in our change failure rate, but excluded from Time to Restore. I shall cover the incident in greater detail in a future post.

But how did we achieve such impressive metrics?

By living the DevOps Dream of course!

Data Driven

At Mechanical Rock we believe that the key to successful product delivery is the capability to make data-driven decisions based on experiential learning. We put the right metrics in place and have the discipline to respond to what we learn.

At the highest level, our product goals and accompanying hypotheses provide the barometer for success. But such trailing indicators are insufficient for agile course correction during delivery.

Rather, we focus on leading indicators. Core to our data driven approach are the Software Delivery and Organisational Performance (SDO) metrics:

- Lead Time

- Deployment Frequency

- Time to Resolution

- Change Failure Rate

We capture the Four Key metrics directly from our Delivery Pipeline and operational environment.

We reviewed our progress during regular retrospectives in order to maintain Elite status throughout.

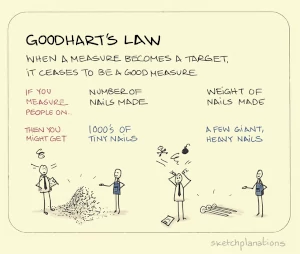

A benefit of the SDO metrics is that they are difficult to game. Game your lead time and you will impact your change failure rate.

We prefer to use metrics to understand the health of our delivery process. To gain a deeper understanding, we also monitor other detailed measures to give us the story behind the headlines. These include:

Using these measures, we eliminate waste within our delivery process, amplify our feedback loops, and continually learn.

Value Stream

The goal for any software value stream is to deliver value. Delivery of value is hard to measure due to the variability of the requirements.

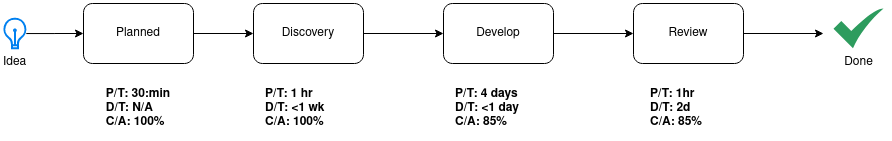

For DevOps Dream, we measured our value stream based on the delivery of Stories. Over the course of development, the lead time to completion averaged 4 days 20 hours.

But we cannot go further without discussing our Definition of Done:

- Does the new feature meet all the acceptance criteria/scenarios set for it?

- Is the build/CI pipeline green?

- Are any new tests added with this change reporting in whatever dashboard you are using?

- Are all the assets required (including BDD/BDI scenarios etc) checked into source control?

- Have you updated any tickets, stories or requests with appropriate comments?

- Have you updated any (external) documentation? (e.g. release notes on the wiki, design docs)

- Have observability requirements been satisfied?

- Has someone eyeballed it in production?

- Has the Product Owner reviewed it?

This is not the same as what is required for developers to merge their code branches with the trunk (pull request process).

You should be able to merge a PR without meeting the DoD. PR is about code quality and review process, not feature completeness. If you combine the two, you end up with long lived branches which, may, lead to integration issues further down the line. Feature toggles, etc allow you to merge work that is not complete. But you don’t want to merge crappy code. – Tim Myerscough, July 2017

On average having committed to a piece of work, the team were able to deliver it.

To production.

In under 1 week.

And that includes discovery time.

To every member of the development team for DevOps Dream:

So proud.

Team Structure

Any organization that designs a system (defined broadly) will produce a design whose structure is a copy of the organization's communication structure. — Melvin E. Conway

Suboptimal team structures set you up for failure. We prefer small, cross-functional teams to maintain a high degree of autonomy. For DevOps Dream, we opted for a team of 5:

- 1 UX Designer / Delivery Lead

- 3 Developers

- 1 Product Owner (part time)

Importantly there are roles we don't call out specifically:

- Tester is not a role we use: Quality is not somebody else's problem.

- Ops/SRE is not a role we use: Operational stability is not somebody else's problem.

Instead, Mechanical Rock developers are 'T-shaped': generalists able to cover all aspects of the DevOps lifecycle but each with their own specialisms such as Web Development, testing or SRE.

The team was responsible for the whole lifecycle. The lack of hand-offs eliminated waste, and drove home the importance of quality.

Planning

We have looked at our own product development previously and something we have learned is that trying to build them using an opportunistic approach, when people have free time, doesn't work. For DevOps Dream, we chose to commit: the core development team was protected from external pressures to enable continuity and focus. Delivery was broken down into 1 week sprints, culminating in a Friday afternoon showcase to the wider Mechanical Rock stakeholders.

When approaching planning, I had a few aims:

- Firstly, planning is boring. We have all been in planning sessions that seem to go on forever. For DevOps Dream, I wanted planning to be quick, yet equally effective.

- Planning alone does not provide any value, therefore planning should be deferred until as late as reasonably possible.

- Planning has different goals for different audiences. High level planning is important for wider stakeholder engagement and budget management. Detailed planning enables the team to turn high level hand-waviness into reality. Therefore, any effort spent on planning was targeted to the audience it was for.

- We operate on a fixed cost, variable scope model: we had a timebox for delivery, within that timebox we would work on the highest priority items. At the end of the timebox, we evaluate whether to invest more time.

The last point is worth a bit more exploration. We see many clients that are constrained by organisational budgetary processes. Long, detailed, budgetary approval processes lead to protracted discovery and pre-planning which in turn harms agility and causes re-work. By having a more flexible approach you can retain cost control, focus on value and defer planning until as late as reasonably possible. Using this approach, we were able to have our first commits to a working system within 1 week from initial project kickoff.

We split planning into the following focus areas:

- High level roadmap - As we kicked off the project, we developed a high-level delivery roadmap, planning for UX discovery, development, beta-testing, initial release and marketing. The picture at this stage was extremely fuzzy, but provided us with the end goal.

- Forward planning - As product owner, I worked with the delivery lead to prioritise the backlog and roughly plan 4-5 sprints of work. The aim of the high level planning was not to hold to a schedule, but to get a rough feel for the size of the problem, knowing things would crop up and push things to the right. Anything not assigned to a sprint was prioritised and placed in the backlog. As contingency, after every 3-4 sprints of pre-planned work, I left a sprint totally unallocated - to cater for reality whilst still enabling a high level view. As development progressed and a product started to form, I used JIRA's version feature to differentiate features required for Beta Testing, Public Release and Below the line - the things we were unlikely to get to.

- Course correction - On an ad-hoc basis, following a need/discussion highlighted during our daily stand-ups, I would review the overall priority list in order to tweak things as development progressed. This would generally occur once every couple of sprints or so. Having previously marked items with an appropriate release meant this process was quick and painless, usually taking less than 10 minutes.

- Sprint planning - Planning for the following week was performed on a Friday, directly after showcase. The team reviewed current progress and considered items suggested for the following sprint. Since items had already been prioritised, this was simply a matter of moving the commitment up/down based on the teams estimation of how much they felt they could achieve. Items were never allocated to individuals and sprint planning rarely took longer than 10 minutes.

- Task Breakdown - Sprint planning was performed at a story level only - each one a promise of a conversation. During each sprint, when an individual took ownership for a ticket, they would be responsible for breaking down the story into appropriate sub-tasks that made sense for them - the subtasks were what we mainly discussed during standups.

At the risk of labouring a point: all planning activities generally took less than 30 minutes per week.

One thing I see that regularly results in protracted planning is estimation. Teams spend hours of their lives that they can't get back estimating work. The reasons are often relate to control - either motivated by command and control structures looking to hold people to a delivery schedule based on guesswork, or constrained by a budgetry process that requires detailed tracability, allocation and approval.

For DevOps Dream, we essentially followed #NoEstimates. Whilst having had a general appreciation for what "No Estimates" was about for years, I must confess that I had never actually read the original post until I started writing this piece. Whilst I would not try to suggest a case for synchronicity, we followed the approach of Woody's original post very closely. It's not that we never do any estimation, but rather that we never wrote them down or spend much time over them.

As Product Owner I already had a relatively clear picture of the order of importance of stories. The effort involved in a particular story was, usually, unlikely to effect it's priority that much meaning any discussion was waste. As we discovered new stories, I would ask questions like "How long do you reckon X will take? Days or weeks?" or "Is story X bigger, smaller or about the same to story Y?". The answer to these two simple questions provided enough data to affect priorities. Sometimes, something that was deemed simple would bubble up the priority list. Less frequently, a story was de-prioritised after the team felt it would be a lot of work.

Trust is essential: as Product Owner, I had trust in the team to develop features as quickly and sustainably as possible. The team trusted me not to hold them to account for an estimate based on a 30 second conversation. The result: I was able to quickly and effectively plan upcoming work, the team was able to do "less talky talky, and more worky worky". Early discussions were much more focussed on "the what", rather than "the how" or "how long" which enabled the team to strive for simplicity and push back for an alternative simpler version.

I would also like to linger to talk about our daily stand-ups. I have experienced many teams that follow Scrum ceremonies and call them agile. If your daily stand up takes 30+ minutes and is a creeping death as each person recounts "Yesterday I .... Today I'm .... No blockers." - sorry, but you're doing it wrong. You have a board somewhere - USE IT! During stand ups, we walk the board - right to left: we discuss each item, what is blocking it from moving forward - and most importantly: identifying how to remove the impediment. So less, creeping death, more focussed progress: "Ticket 123 is ready for code review. Who can pick that up this morning?", "I'm stuck with a permissions issue. Who can help me out?". When our stand-ups crept past the 15 minute mark, it was usually due to discussing how to resolve an impediment: technically an 'offline' discussion.

Discovery

Percent Complete and Accurate (%C&A). A quality metric used to measure the degree to which work from an upstream supplier is determined by the downstream customer to be complete and accurate (or error free). In other words, to what degree does the downstream customer need to:

- correct information that is incorrect;

- add missing information that should have been supplied by an upstream supplier; and/or

- clarify information provided. Out of 100 “things” passing to the downstream customer, what percentage of them are complete and accurate and do not require one of the three above actions before completing the task? The number is obtained by asking the immediate, or successive, downstream customer(s) what percentage of the time they receive work that is 100% complete and accurate.

In the value stream above, I showed how our %C&A for discovery is 100%.

We never had to revisit requirements during the delivery process, despite only spending about one hour on discovery.

How?

Simple:

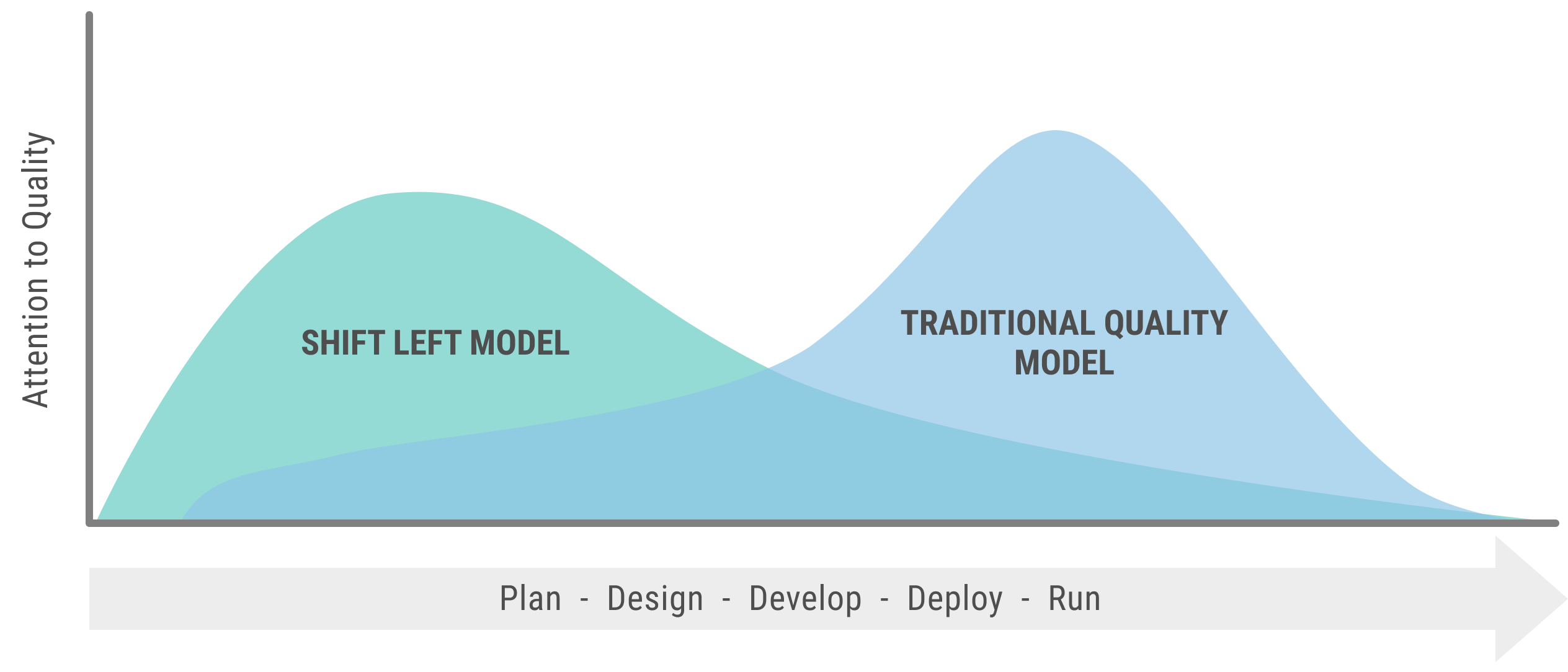

- Breaking work down into small increments.

- Shift learning left using Behaviour Driven Development (BDD).

- Use feedback loops to influence direction.

At Mechanical Rock, we are experienced practitioners and trainers of Behaviour Driven Development. By experimenting quickly we can reduce the cost of delivery up to 7x.

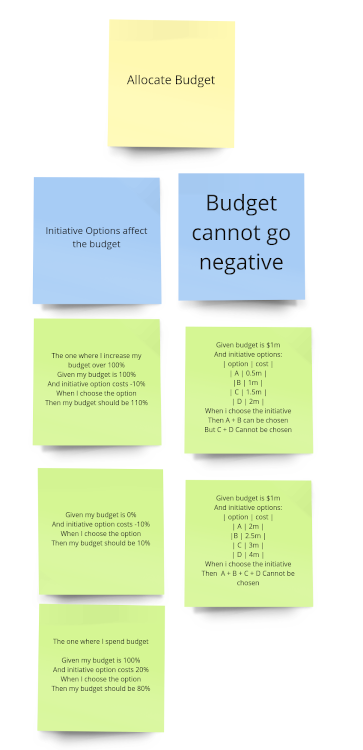

Ordinarily we prefer to run our Example Mapping sessions in person, but COVID-19 added the extra challenge of enforcing remote working. We experimented with a few tools, but have currently settled on Miro. It has the great benefit that all our discovery sessions are in one place, making cross reference easy. The downside was that I often prefer to scribble pictorially for expediency - a picture can tell 1000 words. With online tools we were pushed towards using G-W-T notation.

As Product Owner I tried to focus primarily on the rules. Often I started a session with very little pre-preparation, intentionally. Having the flexibility on the requirement, I wanted to truly discover the rules with the team. We would often explore different options under a story. I would create contradictory rules and challenge the team to come up with different examples. I'd like to thank the team again for indulging me on this and bearing with me as we explored the problem, only for us to throw away much of what we discussed. But I'd much prefer to fail fast after a few minutes prototyping with concrete examples, rather than build the wrong thing.

I also used our example mapping sessions as an effective scoping tool.

When exploring game initiatives, we had a lot of ideas for adding depth and difficulty. We explored ideas around changing funding levels of previous year initiatives, extending the effects of initiative funding. This is where estimation was useful - and obvious. We've had some great feedback requesting the feature to change funding levels in subsequent years. We considered this for the original release, but realised it opened a bit of a can of works on complexity. I won't share it here, since it's still in our backlog, so watch this space. Being able to explore the problem see the extent of the complexity, I was able to make an informed judgement to defer the extra complexity until we had a greater understanding of the game - defer the decision to include the feature until the last responsible moment. When we do get round to the feature again, we shall likely have to start the discovery again.

Something that is often misunderstood in traditional requirements capture processes. The value of the discovery process is not a requirements document: it is the understanding gleaned by the development team. If the people involved in discovery are different from those building the software - the value is limited. Either the development team have to do their own discovery again to gain their own understanding, or they need to process the information from a third party, increasing the risk of gaps or misunderstandings.

In our value stream above, our %C&A for discovery is 100%. That does not mean we never iterated on an idea, nor changed our minds. Far from it. But when we committed to a story, we always followed through to delivery.

There were many times where example mapping was insufficient - we can't explore when we don't know which option to choose. In these instances a different approach was required: hypothesis driven development.

We had quite a few sleepless nights working on the difficulty of the game. And something we eventually cracked very close to release - 1 week prior. We could see the core of the game was there, but it was just too easy. I couldn't get fired, even if I tried. I picked an average strategy and smashed Elite category. But how could we make the game harder? We had plenty of levers, but weren't sure which ones to pull. Time to experiment:

Some experiments failed:

We believe that limiting the number of initiatives a player can choose Will make the game harder We know we have been successful when 500 runs reduce the Elite win rate to < 10%

Limiting the initiatives did indeed make the game harder, but it also hurt the gameplay. It made the game feel too much like a crapshoot.

Some were partially successful:

We believe that introducing black swan events Will make the game harder We know we have been successful when 500 runs reduce the Elite win rate to < 10%

Our first attempt was a little too successful: beware the "Killer Feature!". Instantly fired no matter what choice you made! After a few iterations, we were able to settle on a number of events that definitely increased the difficulty. They also encouraged replay - if you were unlucky to get one of these events then you were extremely unlikely to succeed. However, these events are unlikely, and without them the game was still way too easy. With other tweaks, we have since been able to normalise most of the events in order to avoid wild swings.

Some were a clear success:

We believe that limiting budget across all years

Will make the game harder

We know we have been successful when 500 runs reduce the Elite win rate to < 10%

We've received a lot of feedback on this. Some people have found having their budget fixed for three years confusing. Originally, it wasn't the case, but experiments showed that this provided the single biggest jump in both difficulty and engaging gameplay.

Initiatives are your strategy levers to pull. When the budget reset, you just had too many options to play with, making it easy to win. On the surface, it may seem similar to "limiting the number of initiatives a player can choose" above, but actually provides a far greater depth of gameplay. When your options are limited, but each option is available to you - then the strategy is clear: pick the top three initiatives. With the budget limit you are now faced with real tradeoffs. Want an aggressive cloud migration strategy? Sure, but it means you won't be able to fund product teams as part of your DevOps transformation.

Thanks again to everyone that has given us feedback, but this is one aspect of the game we don't plan on changing any time soon.

As an additional benefit, the budget limit also directly contributes to our engagement goal: in order to succeed at the highest levels you have to learn the game and optimise your strategy.

Delivery

The culmination of the above, along with our rigorous technical practices, enabled us to deliver a consistent flow of work into production.

Through continuous deployment, separating deployment from release, the lead time for change to production averaged < 1 hour from commit to trunk.

The team averaged 2.5 deployments to production per day. The peak was 9 deployments to production in one day.

Did I mention...?

But that headline is a story for another day...

Launch

We originally planned to launch in November 2020. Instead, we launched on 19th August 2020 over two months ahead of our original schedule.

Technically, we actually released towards the end of June. We just didn't tell anyone. By dark launching early we brought forward the, limited, pain of operational support. We had to ensure that updates were delivered properly and didn't cause any issues for existing users.

We were able to bring our beta testing programme forward using our production system. Yes it had a few warts, and was too easy - but we were able to gain crucial external feedback that we were on the right track. DevOps Dream was a significant investment: a high opportunity cost. Validating early that we were on the right track and should continue that investment was important. In future, we plan to validate our ideas externally even earlier - within weeks of inception where possible.

Through our commitment to Continuous Deployment the path to release was never a death march. Hamish, rightfully, challenged me regularly on when we would release. "As soon as possible" was always my reply. Until it wasn't.

I'd like to thank everyone at Mechanical Rock for helping make DevOps Dream a reality. You all played a part.

In particular, I'd like to thank the development team: Karen Cheng, JK Gunnink, Natalie Laing and Nadia Reyhani.

Awesome work guys!

I'd also like to thank our beta testers for all your valuable input: Brian Foody, Sam Stoddard, Luke Evans, Valeria Spirovski, Ian Hughes, Peter Maddison, Matt James, Esther Krogdahl and Faye Jakovecevic.

If you'd like to live your own DevOps Dream, let's chat